[ UPDATE July 2016 – I no longer subscribe completely to the concept of capacity planning, at least to this level of detail. I will keep this post available, but I will not maintain the fancy spreadsheet 😉 It’s fun to geek out with numbers and formulas, but we could do better having meaningful conversations with our teams. ]

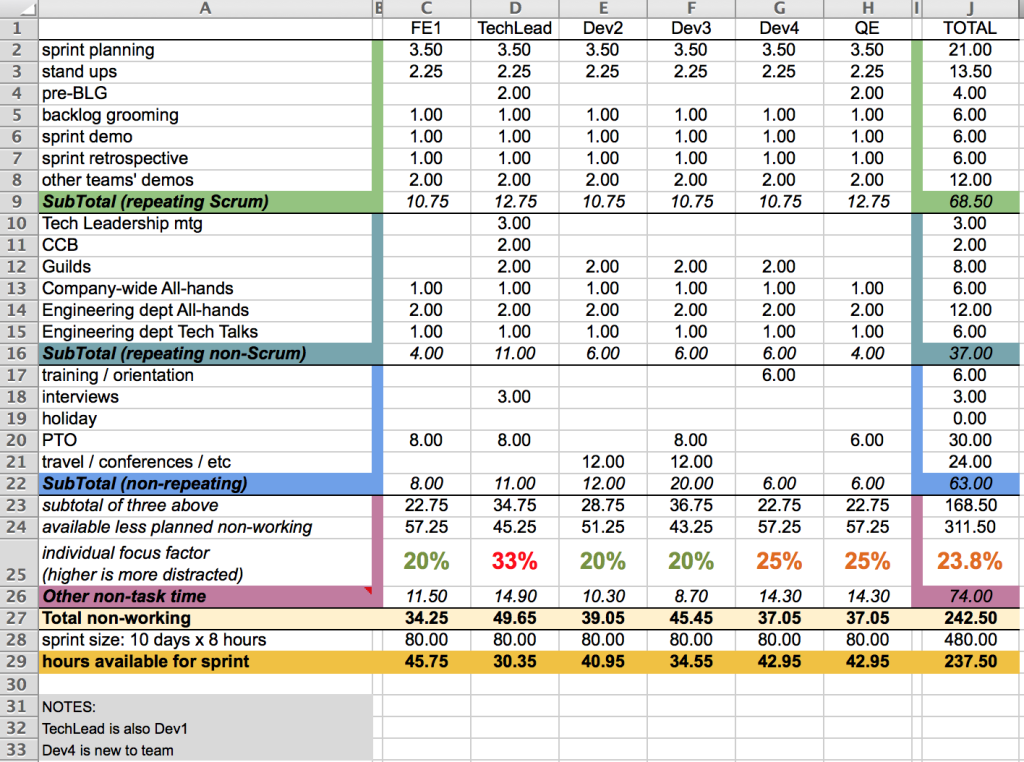

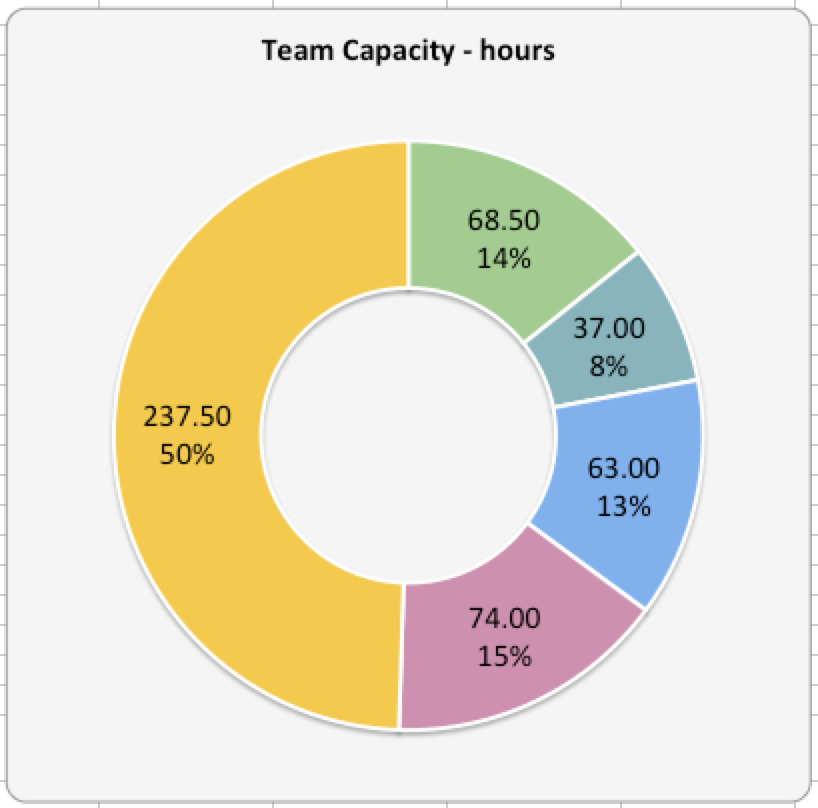

The topic of Capacity Planning came up in a recent coffee, and I decided to introduce it to my new team. I just developed a spreadsheet (illustration below) that helps make visible the number of hours that each team member is committed to for various activities not related to actual work on user stories and defects. The purpose for doing this was to make everyone aware of their overhead before they commit to a sprint.

I was introduced to the concept of making capacity transparent at the start of each sprint when SendGrid did the initial Agile transformation. I was especially drawn to the focus factor (though we didn’t use that term at SG) which accounts for the hard-to-quantify time that an individual loses each day to tasks such as checking emails, impromptu discussions, unplanned meetings, helping teammates, etc. For focus factor, we plugged in a flat value of about 25% of each person’s day, but the more I consider it, I now prefer using a range (eg. from 15-30%) specific to each team member. This factor may also may change over time (eg. sprint to sprint or day to day).

The hours in the worksheet (full size image below) are all based on a two-week sprint, so how many hours for activity x are consumed in 14 days.

I’m going to walk through the rows in some detail here:

- Columns C – H represent six individual contributors on a Scrum team. The team’s Tech Lead attends more meetings and is interrupted more than other members. Dev4 is a new team member and is attending orientations and trainings.

- Rows 2 – 8 are related to Scrum ceremonies that are repeating and predictable over the two-week sprint.

- Rows 10 – 15 are related to non-Scrum activities scheduled by the company, department or guilds that are repeating and predictable over the two-week sprint.

- Rows 17 – 21 are non-repeating and unpredictable. The ScrumMaster solicits each member’s hours in this category at the start of the Sprint Planning session.

- Row 26 represents the unknown, unquantifiable “soup” that consumes our working days (described above). The focus factor (row 25) changes for each team member, and the higher the percent value, the more the member is expected to be distracted. This percent value is applied to the hours remaining outside of those already accounted for in the above three categories.

- Row 27 is the sum (in hours) of each of the above four categories.

Note that (for this sample team) no account is made for any team members splitting their time between projects (eg. the FE developer is 100% allocated to this team). Also, the focus factor isn’t adjusted for multi-tasking between an unreasonable number of stories (ie. this model assumes an individual WIP limit of 1 or 2) with the possible exception of the Tech Lead.

[update 5/15/15] Here’s a download of the Team Capacity Worksheet (.xls). I offer this download with no guarantees that it will work on your OS, and I will not be updating it or converting it to other formats.

I welcome comments below or on twitter using #capacityworksheet